Long-COVID-19–Integrative Approach to Prevention and Treatment

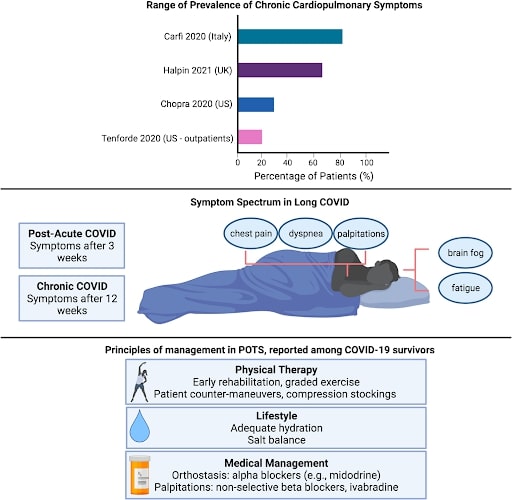

Long-COVID names and definitions have evolved. The National Institutes of Health refers to post-acute sequelae SARSCoV-19 (PASC) for folks with persistent symptoms 28 days after diagnosis. People with post-acute COVID syndrome (PACS) have persistent symptoms 3 weeks after diagnosis while those with chronic COVID (long-COVID) have symptoms 12 weeks after diagnosis.

Between 10% and 30% of people infected with the SARS-CoV-19 virus may feel long-term symptoms. So, between 5.4 and 17.9 million globally and about 700 000 in the US have long-COVID. The largest study of long COVID to date queried 2 million patients with a history of COVID-19 and found that 23.2% had at least one post-COVID condition 30 days or more after their initial diagnosis.

Those with more severe COVID disease requiring hospitalization and those with pre-existing health conditions like obesity, hypertension, and mental health conditions are more likely to experience symptoms. While older individuals with multiple comorbidities are at higher risk of long COVID, approximately 20% of young individuals, ages 18–34 and without comorbid conditions, also continue to report ongoing symptoms at 14–21 days.

One survey of 3762 people from 56 countries with long COVID symptoms finds that 45.2% require a reduced work schedule and 22.3% are unable to work because of their health. An economic analysis of long COVID estimates that COVID-related disability can be responsible for as much as a third of the overall COVID-19 health care burden around the globe. The long-COVID patients with illnesses lasting more than 28 days are found to have up to 205 different symptoms in 10 organ systems.

The more commonly reported symptoms span a large breadth of cardiopulmonary and neurologic concerns including fatigue, muscle aches, palpitations, chest pain, breathlessness, and brain fog. Regarding specific cardiovascular symptoms, approximately 20% of individuals reported chest pain and 14% reported palpitations at 60 days. An association between COVID-19 and postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is characterized by a change in heart rate with positional change, often accompanied by palpitations and decreased exercise tolerance.

The many symptoms may have multiple causes:

- Chronic low level of inflammation in the brain, heart, muscle, and nerves.

- An immune response dysregulation and autoimmune condition in which the body makes antibodies that attack the brain.

- Dysfunction of special receptors in the heart and lungs.

- Widespread clotting and blood vessel dysfunction.

- Autonomic nervous system abnormalities leading to decreased blood flow to the brain.

- An undetectable reservoir of infectious or noninfectious virus that continues to trigger an immune response.

An integrative medicine approach addresses physical, behavioral, psychosocial, and spiritual needs. By engaging in shared decision-making, identifying life goals, and placing people at the center of their care plan, the integrative approach effects positive outcomes in conditions that do not have clear and specific curative options, such as chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, chronic pain, and post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome. Similarly, symptom severity in long-COVID may be reduced or prevented by restoring the same balance. The integrative approach focuses on combating inflammation, repairing lung injury, repleting nutritional deficiencies, reducing chronic stress, and mitigating fatigue. Lifestyle changes that prevent and treat long-COVID include:

- An anti-inflammatory diet.

- A mindfulness plan, such as yoga, journaling, meditation, guided imagery.

- Breathing exercises.

- Physical exercise.

Cardio Care sure the breathing exercises may help with anxiety, stress, but can also improve the breathlessness post-COVID folks often feel with scarred lungs.

An anti-inflammatory diet combines the traditional Mediterranean and Asian eating patterns and is characterized by high consumption of vegetables, fruit, legumes, fish, lean protein, whole grains, spices, nuts, and seeds, and low consumption of both refined grains and processed foods. Various nutrient components of an anti-inflammatory diet, such as monosaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids are associated with decreased inflammation. Fruits and vegetables are the main dietary sources of vitamins and minerals and provide anti-inflammatory and antioxidant phytochemicals. As a result, the whole foods diet may improve respiratory function by reducing airway inflammation and oxidative stress. The USDA recognizes produce subgroups as follows: dark green, red, and orange vegetables, legumes, starchy vegetables, and fruit. Eating produce from all sub-groups is important to obtain a full spectrum of these phytochemicals. The USDA MyPlate guidelines recommend that half of each meal is fruit and vegetables.

In addition to nutrition, supplements may also help with long-COVID. Vitamin D (3000-5000 IU per day) has anti-viral, anti-inflammatory, and immune-enhancing actions in the lungs. Glutathione (250-1000 mg per day) is the body’s primary endogenous antioxidant and is the most abundant antioxidant in the lung epithelium. Melatonin (5-10 mg per day) is a potent endogenous antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immune-enhancing molecule.

Cordyceps (1.5-3 g per day) is a medicinal mushroom with a long tradition of use due to its antioxidant, antitumor, anti-inflammatory, and anti-microbial actions. Aged garlic extract (7 g per day) is a source of organosulfur compounds which downregulate nuclear factor-kappa B (NFkB) and reduce the expression of many inflammatory cytokines.

Contemplative practices, breathing exercises, and physical exercises are part of the integrative approach for preventing and treating long-COVID. Qigong is an ancient practice of meditation, breathing, and slow movements that improves pulmonary function. The four mechanisms with Qigong for a long-COVID benefit are stress management, strengthening respiratory muscles, reducing inflammation, and enhancing immune function. Breathing exercises that help with anxiety and respiratory rehabilitation include diaphragmatic (belly) breathing, pursed-lip breathing, pranayama, and tai chi breathwork. Once recovered from acute symptoms of COVID, exercise needs to gradually increase starting with stretching, light muscle strengthening, then moderate cardiovascular exercise. Folks should avoid high-intensity training until fully recovered.

Inflammation and increased metabolic and oxygen demand are thought to contribute

to persistent cardiovascular symptoms. A conventional medicine approach may be more helpful for treating the long-COVID symptoms of chest pain initially with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (Indocin and colchicine) followed by steroids if needed. The management of POTS and dysautonomia includes education, exercise, and salt and fluid repletion. Medications such as midodrine can improve vascular tone, while beta-blockers can help manage palpitations.

I will conclude by emphasizing that the most effective approach to preventing long-COVID is to prevent infection from COVID-19 and the different variants. Follow the Centers for Disease Control guidelines regarding masks, social distancing, vaccinations, and boosters. There are also helping support groups for long-COVID and trying to make sense of long COVID syndrome.

For additional information don’t hesitate to contact us.

References:

- Alschuler, L Integrative medicine considerations for convalescence from mild-to-moderate COVID-19 disease, Explore 000(2020)

- Chilazi, M, COVID, and Cardiovascular Disease: What We Know in 2021, Current Atherosclerosis Reports (2021) 23:37

- Roth, A, Addressing the Long COVID Crisis: Integrative Health and Long COVID

- Global Advances in Health and Medicine Volume 10: 1–6, October 13, 2021

LOCATIONS

Contact us for more information.